Pre-Civil War Slave Revolts and Abolitionist

Movements

In the United States

San Miguel de

Gualdape – 1526

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA]

San Miguel

de Gualdape was the first European settlement in the North

American continent, founded in 1526 by Spanish explorer Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón. The settlers

lasted only through three months of winter before abandoning the site in early

1527.

Ayllón had brought a group of

Africans to labor at the mission, to clear ground and erect the buildings. This

was the first time that Spanish colonists had used African slaves on the North

American continent. During a period of internal political disputes among the

settlers, the slaves rebelled. This 1526 incident is the first documented slave

rebellion in North America.

New York

Slave Revolt – 1712

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA]

The New

York Slave Revolt of 1712 was an uprising in New York City of 23 enslaved

Africans who killed nine whites and injured another six. More than three times

that number of blacks, 70, were arrested and jailed. Of these, 27 were put on

trial, and 21 convicted and executed.

While in

the early 1700s, New York had one of the largest slave populations of any of

England’s colonies, slavery in New York differed from some of the other

colonies because there were no large plantations. Enslaved Africans lived near

each other, making communication easy. They also often worked among free

blacks, a situation that did not exist on most plantations. Slaves in the city

could communicate and plan a conspiracy more easily than among those on

plantations. They were kept under abusive and harsh conditions, and naturally

resented their treatment.

The men

gathered on the night of April 6, 1712, and set fire to a building on Maiden Lane near Broadway. While the white colonists tried to put out the fire, the

enslaved African Americans, armed with guns, hatchets, and swords, attacked

them and ran off.

Seventy

blacks were arrested and put in jail. Six are reported to have committed

suicide. Twenty-seven were put on trial, 21 of whom were convicted and

sentenced to death. Twenty were burned to death and one was executed on a

breaking wheel. This was a form of punishment no longer used on whites at the

time. The severity of punishment was in reaction to white slaveowners'

fear of insurrection by slaves.

After the

revolt, laws governing the lives of blacks in New York were made more

restrictive. African Americans were not permitted to gather in groups of more

than three, they were not permitted to carry firearms, and gambling was

outlawed. Other crimes, such as property damage, rape, and conspiracy to kill,

were made punishable by death. Free blacks were no longer allowed to own land.

Slave owners who decided to free their slaves were required to pay a tax of

£200, a price much higher than the price of a slave.

![]()

Stono Rebellion – 1739

[FROM WIKIPEDIA]

With the

increase in slaves, colonists tried to regulate their relations, but there was

always negotiation in this process. Slaves resisted by running away, work

slowdowns and revolts. In this case, the slaves may have been inspired by

several factors to mount their rebellion. Spanish Florida offered freedom to

slaves escaped from British colonies; the Spanish had issued a proclamation and

had agents spread the word about giving freedom and land to slaves who got to

Florida. Tensions between England and Spain over territory in North America

made slaves hopeful of reaching Spanish territory, particularly the free black

community of Fort Mose, founded in 1738 outside St.

Augustine. Stono was just 50 miles from the Florida

line.

In

addition, a malaria epidemic had killed many whites in Charleston, weakening

the power of slaveholders. Lastly, historians have suggested the slaves

organized their revolt to take place on Sunday, when planters would be occupied

in church and might be unarmed. The Security Act of 1739 (which required all

white males to carry arms even to church on Sundays) had been passed in August

but not fully taken effect; penalties were supposed to begin after 29

September.

Jemmy, the leader of the revolt, was a

literate slave described in an eyewitness account as "Angolan".

Historian John K. Thornton has noted that, because of patterns of trade, he was

more likely from the Kingdom of Kongo in west Central

Africa, which had long had relations with Portuguese traders. His cohort of 20 slaves were also called "Angolan",

and likely also Kongolese. The slaves were described

as Catholic, and some spoke Portuguese, learned from the traders operating in

the Kongo Empire at the time. The patterns of trade

and the fact that the Kongo was a Catholic nation

point to their origin there. The Kingdom of Kongo had

voluntarily converted to Catholicism in 1491; by the 18th century, the religion

was a fundamental part of its citizens' identity. The nation had independent

relations with Rome. Slavery predated the introduction of Christianity to the

royal court of Kongo, was regulated by the Kingdom

and was still practiced as late as the 1870s.

Portuguese

was the language of trade as well as one of the languages of educated people in

Kongo. The Portuguese-speaking slaves in South

Carolina were more likely to learn about offers of freedom by Spanish agents.

They would also have been attracted to the Catholicism of Spanish Florida.

Because Kongo had been undergoing civil wars, more

people had been captured and sold into slavery in recent years, among them

trained soldiers. It is likely that Jemmy and his

rebel cohort were such military men, as they fought hard against the militia

when they were caught, and were able to kill 20 men.

On Sunday,

10 September 1739, Jemmy gathered 20 enslaved

Africans near the Stono River, 20 miles (30 km)

southwest of Charleston. This date was important to them as the Catholic

celebration of the Virgin Mary's nativity; like the religious symbols they

used, taking action on this date connected their Catholic past with present

purpose. The Africans marched down the roadway with a banner that read

"Liberty!", and chanted the same word in unison. They attacked Hutchenson's store at the Stono

River Bridge, killing two storekeepers and seizing weapons and ammunition.

Raising a

flag, the slaves proceeded south toward Spanish Florida, a well-known refuge

for escapees. On the way, they gathered more recruits, sometimes reluctant

ones, for a total of 80. They burned seven plantations and killed 20–25 whites

along the way. South Carolina's Lieutenant Governor William Bull and four of

his friends came across the group while on horseback. They left to warn other

slaveholders. Rallying a militia of planters and slaveholders, the colonists

traveled to confront Jemmy and his followers.

The next

day, the well-armed and mounted militia, numbering 20–100 men,[citation

needed] caught up with the group of 80 slaves at the Edisto River. In the

ensuing confrontation, 20 whites and 44 slaves were killed. While the slaves

lost, they killed proportionately more whites than was the case in later

rebellions. The colonists mounted the severed heads of the rebels on stakes

along major roadways to serve as warning for other slaves who might consider

revolt. The lieutenant governor hired Chickasaw and Catawba Indians and other

slaves to track down and capture the Africans who had escaped from the battle.

A group of the slaves who escaped fought a pitched battle with a militia a week

later approximately 30 miles (50 km) from the site of the first conflict. The

colonists executed most of the rebellious slaves; they sold other slaves off to

the markets of the West Indies.

![]()

New York

Conspiracy – 1741

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA]

The

Conspiracy of 1741, also known as the Negro Plot of 1741 or the Slave Insurrection

of 1741, was a supposed plot by slaves and poor whites in the British colony of

New York in 1741 to revolt and level New York City with a series of fires.

Historians disagree as to whether such a plot existed and, if there was one,

its scale. During the court cases, the prosecution kept changing the grounds of

accusation, ending with linking the insurrection to a Popish plot of Spanish

and other Catholics.

In 1741

Manhattan had the second-largest slave population of any city in the Thirteen

Colonies after Charleston, South Carolina. Rumors of a conspiracy arose against

a background of economic competition between poor whites and slaves; a severe

winter; war between Britain and Spain, with heightened anti-Catholic and

anti-Spanish feelings; and recent slave revolts in South Carolina and Saint

John in the Caribbean. In March and April 1741, a series of 13 fires erupted in

Lower Manhattan, the most significant one within the walls of Fort George, then

the home of the governor. After another fire at a warehouse, a slave was

arrested after having been seen fleeing it. A 16-year-old Irish indentured

servant, Mary Burton, arrested in a case of stolen goods, testified against the

others as participants in a supposedly growing conspiracy of poor whites and

blacks to burn the city, kill the white men, take the white women for themselves, and elect a new king and governor.

In the

spring of 1741 fear gripped the Manhattan as fires burned all across the

island. The suspected culprits were New York's slaves, some 200 of which were

arrested and tried for conspiracy to burn the town and murder its white

inhabitants. As in the Salem witch trials and the Court examining the Denmark

Vesey plot in Charleston, a few witnesses implicated many other suspects. In

the end, over 100 people were hanged, exiled, or burned at the stake.

Most of the

convicted people were hanged or burnt – how many is uncertain. The bodies of

two supposed ringleaders, Caesar, a slave, and John Hughson, a white cobbler

and tavern keeper, were gibbeted. Their corpses were left to rot in public.

Seventy-two men were deported from New York, sent to Newfoundland, various

islands in the West Indies, and the Madeiras.

![]()

German Coast

Uprising (Orleans Territory) – 1811

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA, Except Where Noted in

Italics]

The 1811

German Coast Uprising was a revolt of black slaves in parts of the Territory of Orleans on January 8–10, 1811. A group of conspirators met on January 6,

1811. It was a period when work had relaxed on the plantations after the fierce

weeks of the sugar harvest and processing. As planter James Brown testified

weeks later, "the black Quamana [Kwamena, meaning "born on Saturday"], owned by

Mr. Brown, and the mulatto Harry, owned by Messrs. Kenner & Henderson, were

at the home of Manuel Andry on the night of

Saturday–Sunday of the current month in order to deliberate with the mulatto

Charles Deslondes, chief of the brigands."

Slaves had spread word of the planned uprising among the slaves at plantations

up and down the German Coast.

The revolt

began on January 8 at the André plantation. After striking and badly wounding

Manuel André, the slaves killed his son Gilbert. "An attempt was made to

assassinate me by the stroke of an axe," Manuel André wrote. "My poor

son has been ferociously murdered by a horde of brigands who from my plantation

to that of Mr. Fortier have committed every kind of mischief and excesses,

which can be expected from a gang of atrocious bandits of that nature."

The

rebellion gained momentum quickly. The 15 or so slaves at the André plantation,

approximately 30 miles upriver from New Orleans, joined another eight slaves

from the next-door plantation of the widows of Jacques and Georges Deslondes. This was the home plantation of Charles Deslondes, a field laborer later described by one of the

captured slaves as the "principal chief of the brigands." Small

groups of slaves joined from every plantation which the rebels passed.

Witnesses remarked on their organized march. Although they carried mostly

pikes, hoes and axes but few firearms, they marched to drums while some carried

flags. From 10–25% of any given plantation's slave population joined with them.

At the

plantation of James Brown, Kook, one of the most active participants and key

figures in the story of the uprising, joined the insurrection. At the next

plantation down, Kook attacked and killed François Trépagnier

with an axe. He was the second and last planter killed in the rebellion. After

the band of slaves passed the LaBranche plantation,

they stopped at the home of the local doctor. Finding the doctor gone, Kook set

his house on fire.

Some

planters testified at the trials in parish courts that they were warned by

their slaves of the uprising. Others regularly stayed in New Orleans, where

many had townhouses, and trusted their plantations to be run by overseers. Planters

quickly crossed the Mississippi River to escape the insurrection and to raise a

militia.

As the

slave party moved downriver, they passed larger plantations, from which many

slaves joined them. Numerous slaves joined the insurrection from the Meuillion plantation, the largest and wealthiest plantation

on the German Coast. The rebels laid waste to Meuillion's

house. They tried to set it on fire, but a slave named Bazile

fought the fire and saved the house.

After

nightfall the slaves reached Cannes-Brulées, about 15

miles northwest of New Orleans. The men had traveled between 14 and 22 miles, a

march that probably took them seven to ten hours. By

some accounts, they numbered "some 200 slaves," although other

accounts estimated up to 500. As typical of revolts of most classes, free or

slave, the insurgent slaves were mostly young men between the ages of 20 and

30. They represented primarily lower-skilled occupations on the sugar

plantations, where slaves labored in difficult conditions. The uprising occurred

on the east bank of the Mississippi River in what are now St. John the Baptist

and St. Charles Parishes, Louisiana. While the slave insurgency was the

largest in US history, the rebels killed only two white men. Confrontations with militia and executions after trial killed

ninety-five black people.

Between 64

and 125 enslaved men marched from sugar plantations near present-day LaPlace on the German Coast toward the city of New Orleans.

They collected more men along the way. Some accounts claimed a total of 200–500

slaves participated. During their two-day, twenty-mile march, the men burned

five plantation houses (three completely), several sugarhouses, and crops. They

were armed mostly with hand tools.

White men

led by officials of the territory formed militia companies to hunt down and

kill the insurgents. Over the next two weeks, white planters and officials

interrogated, tried and executed an additional 44 insurgents who had been

captured. Executions were by hanging or decapitation. Whites displayed the

bodies as a warning to intimidate slaves. The heads of some were put on pikes

and displayed at plantations.

After being

injured, Col. André went to the other side of the river to round up a militia

organized by planters, who began pursuing the slave rebels.

By noon on

January 9, the residents of New Orleans had heard of the insurrection on the

German Coast. Over the next six hours, General Wade Hampton I, Commodore John

Shaw, and Governor William C.C. Claiborne sent two companies of volunteer militia,

30 regular troops, and a detachment of 40 seamen to fight the slaves.

By about 4

a.m., the troops reached the plantation of Jacques Fortier, where Hampton

thought the insurgents had encamped for the night. The insurgents had left

hours before Hampton's arrival and started back upriver. Over the next few

hours, they traveled about 15 miles back up the coast and neared the plantation

of Bernard Bernoudy.

There,

planter Charles Perret, under the command of the

badly injured André and in cooperation with Judge Saint Martin, had assembled a

militia of about 80 men from the opposite side of the river. At about 9

o'clock, this second militia discovered the slaves moving toward high ground on

the Bernoudy estate. Perret

ordered the militia to attack the slaves. Perret

later wrote that there were about 200 slaves, about half on horseback. (Most

accounts said only the leaders were mounted, and historians believe it unlikely

the slaves could have gathered so many mounts.)

The battle

was brief. Within a half-hour of the attack, 40 to 45 slaves had been killed

and the remainder slipped away into the woods. Perret

and Andrée's militia tried to pursue slaves into the

woods and swamps, but it was difficult territory.

On January

11, the militia captured Charles Deslondes, whom

André considered "the principal leader of the bandits." The militia

did not hold him for trial or interrogation. Samuel Hambleton

described Deslonde's fate: "Charles [Deslondes] had his Hands chopped off then shot in one thigh

& then the other, until they were both broken – then shot in the Body and

before he had expired was put into a bundle of straw and roasted!"

Having

suppressed the insurrection, the planters and government officials continued to

search for slaves who had escaped. Those captured were interrogated. Officials

conducted two sets of trials, one at Destrehan Plantation owned by Jean Noel Destréhan and one in New Orleans. The Destréhan

trial, run by the parish court resulted in the execution of 18 slaves, whose

heads were put on pikes. The plantation displayed the bodies of the dead rebels

to intimidate other slaves. One observer wrote, "Their Heads ... decorate

our Levée, all the way up the coast, I am told they

look like crows sitting on long poles." By the end of January, around

100 dismembered bodies decorated the levee from the Place d’Armes

in the center of New Orleans forty miles along the River Road into the heart of

the plantation district. . . .Planters wanted to make sure that anyone who

might empathize with the revolutionaries, anyone who wanted to see the dead as

martyrs, would have to recon with the image of

rotting corpses. American Uprising: The Untold Story of

America’s Largest Slave Revolt, by Damiel Rasmussen. Harper Collins, New

York, NY. 2011. Pp. 147-149.

The trials

in New Orleans, also in the local court, resulted in the conviction and summary

executions of 11 more slaves. Three of these were publicly hanged in the Place d'Armes, now Jackson Square, and their heads were put up to

decorate the city's gates.

U.S.

territorial law provided no appeal from a parish court's ruling, even in cases

involving imposition of a death sentence on an enslaved individual. Governor

Claiborne, recognizing that fact, wrote to the judges of each court that he was

willing to extend executive clemency (“in all cases where circumstances suggest

the exercise of mercy a recommendation to that effect from the Court and Jury,

will induce the Governor to extend to the convict a pardon.”) In fact, Gov.

Claiborne did commute two death sentences, those of Henry, and of Theodore,

each referred by the Orleans Parish court. No record has been found of any

referral from the court in St. Charles Parish, or of any refusal by the Governor

of any application for clemency.

Some

accounts of the events erroneously ascribe greater participation in the

resultant deaths of the enslaved men both to Claiborne and to the U.S. Army. In

fact, the territorial legal "superstructure" in place for the United

States, i.e., the Superior Court, had no role in the trials, which were

conducted solely by the parish courts, comprising the judge and a jury of

planters. The U.S. Army arrived too late on the scene, after

"volunteers" had killed many of the alleged insurgents. General

Hampton's January 16, 1811, report to the Secretary of War describes having his

forces in place, prepared to advance, but that the enslaved individuals slipped

out in the night "in great silence" and were subsequently attacked

"five leagues" away, not by the Army and not by the militia, but by

"a spirited party of Young Men from the opposite side of the river."

Whites

killed about a total of 95 slaves at the time of the insurrection, and by

execution after trials as a result of this revolt. From the trial records, most

of the leaders appeared to have been mixed-race Creoles or mulattoes, although

numerous slaves in the group were native-born Africans. These trials were not meant for the benefit of the slaves, but rather

to present the powerful as legitimately, ethically, and rightly powerful. . .

.[T]he only purpose of the questioning was as the preamble to a trial whose end

was clear from the beginning; the quick execution of all slaves involved in the

insurrection. Ibid., 153.

Fifty-six

of the slaves captured on the 10th and involved in the revolt were returned to

their masters, who may have punished them but wanted their valuable laborers

back to work. Thirty more slaves were captured, but the whites determined they

had been forced to join the revolt by Charles Deslondes

and his men, and returned them to their masters.

The heirs

of Meuillon petitioned the legislature for permission

to free the mulatto slave Bazile, who had worked to

preserve his master's plantation. Not all the slaves supported insurrection,

knowing the trouble it could bring.

As was

typical of American slave insurrections, the uprising was short-lived and

quickly crushed by local white forces; it lasted only a couple of days and did

not overcome local authorities. Showing planter influence, the legislature of

the Orleans Territory approved compensation of $300 to planters for each slave

killed or executed. The Orleans Territory accepted the continued presence of US

military troops after the revolt, as they were grateful for their presence. The

insurrection was covered by national press, with Northerners seeing it arising

out of the wrongs suffered under slavery.

No state or

federal historical marker commemorates the insurrection, though it is mentioned

on the marker for the Woodland Plantation (formerly Andre Plantation):

"Major 1811 slave uprising organized here." Despite its size and

connection to the French and Haitian revolutions, the rebellion is not thoroughly covered in history books. As

late as 1923, however, older black men "still relate[d] the story of the

slave insurrection of 1811 as they heard it from their grandfathers."

Since 1995, the African American History Alliance of Louisiana has led an

annual commemoration at Norco in January, where they have been joined by some

descendants of members of the revolt.

![]()

Gabriel

Prosser – 1800

Gabriel

(1776 – October 10, 1800), today commonly—if incorrectly—known as Gabriel

Prosser, was a literate enslaved blacksmith who planned a large slave rebellion

in the Richmond area in the summer of 1800. Information regarding the revolt

was leaked prior to its execution, and he and twenty-five followers were taken

captive and hanged in punishment. In reaction, Virginia and other state

legislatures passed restrictions on free blacks, as well as prohibiting the

education, assembly, and hiring out of slaves, to restrict their chances to

learn and to plan similar rebellions.

Born into

slavery at Brookfield, a tobacco plantation in Henrico County, Virginia,

Gabriel had two brothers, Solomon and Martin. They were all held by Thomas

Prosser, the owner. As Gabriel and Solomon were trained as blacksmiths, their

father may have had that skill. Gabriel was also taught to read and write.

By the

mid-1790s, as Gabriel neared the age of twenty, he stood "six feet two or

three inches high". His long and "bony face, well made", was

marred by the loss of his two front teeth and "two or three scars on his

head". White people as well as blacks regarded the literate young man as

"a fellow of great courage and intellect above his rank in life".

Gabriel

planned the revolt during the spring and summer of 1800. On August 30, 1800,

Gabriel intended to lead slaves into Richmond, but the rebellion was postponed

because of rain. The slaves' owners had suspicion of the uprising, and two

slaves told their owner, Mosby Sheppard, about the plans. He warned Virginia's

Governor, James Monroe, who called out the state militia. Gabriel escaped

downriver to Norfolk, but he was spotted and betrayed there by another slave

for the reward offered by the state. That slave did not receive the full

reward.

Gabriel was

returned to Richmond for questioning, but he did not submit. Gabriel, his two

brothers, and 23 other slaves were hanged.

Gabriel was

a skilled blacksmith who was mostly "hired out" by his owner in

Richmond foundries. Hiring out was the way that slaveholders earned money from

their slaves, whom they needed less for labor as they had reduced the

cultivation of tobacco as a crop. The market for tobacco was depressed, but

Virginia planters also had to deal with depleted soils because of the crop.

Slaveholders leased skilled slaves for jobs available in Virginia industries.

Gabriel would have been stimulated and challenged at the foundries by

interacting with co-workers of European, African and mixed descent. They hoped

Thomas Jefferson's Republicans would liberate them from domination by the

wealthy Federalist merchants of the city.[citation

needed] In that environment, Gabriel also would have heard about the uprising

and struggles of slaves in Saint Domingue.

It is

believed that Gabriel had two white co-conspirators, at least one of whom was

identified as a French national. He found reports that documentary evidence of

their identity or involvement was sent to Governor Monroe but never produced in

court, and suggests that it was to protect the Jefferson's Democratic-Republican

Party. The internal dynamics of Jefferson's and Monroe's party in the 1800

elections were complex. A significant part of the Republican

base were major planters, colleagues of Jefferson and Madison. It is

possible that any sign that white radicals, and particularly Frenchmen, had

supported Gabriel's plan could have cost Jefferson the presidential election of

1800. Slaveholders feared such violent excesses as those related to the French

Revolution after 1789 and the rebellion of slaves in Saint-Domingue.

Gabriel planned to take Governor Monroe hostage to negotiate an end to slavery.

Then he planned to "drink and dine with the merchants of the city".

Gabriel did

not order his followers to kill all whites except Methodists, Quakers and

Frenchmen; rather, he instructed them not to kill any people in those three

categories. During this period, Methodists and Quakers were active missionaries

for manumission, and many slaves had been freed since the end of the Revolution

in part due to their work.[citation needed] The French were considered allies

as they had abolished slavery in their Caribbean colonies in 1794.

Gabriel

initially escaped on a ship owned by a former overseer. It was discovered that

Gabriel was a recently converted Methodist who repeatedly overlooked

information as to Gabriel's true identity. A slave hired out to work on the

ship turned in Gabriel, seeking the reward so that he could purchase his own

freedom. The state paid him only $50, not the $300 advertised.

Gabriel's uprising

was notable not because of its results—the rebellion was quelled before it

could begin—but because of its potential for mass chaos and widespread

violence. In Virginia in 1800, 39.2 percent of the total population were

slaves; they were concentrated on plantations in the Tidewater area and west of

Richmond.[5] No reliable numbers existed regarding

slave and free black conspirators; most likely, the number of men actively

involved numbered only several hundred

In 2002 the

City of Richmond passed a resolution in honor of Gabriel on the 202nd

anniversary of the rebellion. In 2007 Governor Tim Kaine

gave Gabriel and his followers an informal pardon, in recognition that his

cause, "the end of slavery and the furtherance of equality for all

people—has prevailed in the light of history".

![]()

Igbo Landing

– 1803

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA]

In May 1803

a shipload of seized West Africans, upon surviving the middle passage, were

landed by US-paid captors in Savannah by slave ship, to be auctioned off at one

of the local slave markets. The ship's enslaved passengers included a number of

Igbo people from what is now Nigeria. The Igbo were known by planters and

slavers of the American South for being fiercely independent and more unwilling

to tolerate chattel slavery.

The group of 75 Igbo slaves were bought by agents of John Couper and Thomas Spalding for forced labour

on their plantations in St. Simons Island for $100 each. The chained slaves

were packed under the deck of a small vessel named the The

Schooner York to be shipped to the island (other sources write the voyage took

place aboard The Morovia).

During this voyage the Igbo slaves rose up in rebellion taking control of the ship

and drowning their captors in the process causing the grounding of the Morovia in Dunbar

Creek at the site now locally known as Ebo Landing.

The following sequence of events is unclear as there are several versions

concerning the revolt's development, some of which are considered mythological.

Apparently the Africans went ashore and subsequently, under the direction of a

high Igbo chief who was among them walked in unison into the creek singing in

Igbo language "The Water Spirit brought us, the Water Spirit will take us

home", thereby accepting the protection of their God, Chukwu

and death over the alternative of slavery.

Roswell

King, a white overseer on the nearby Pierce Butler plantation, wrote one of the

only contemporary accounts of the incident which states that as soon as the

Igbo landed on St. Simons Island they took to the swamp, committing suicide by

walking into Dunbar Creek. A 19th century Savannah-written account of the event

lists the surname Patterson for the captain of the ship and Roswell King as the

person who recovered the bodies of the drowned. A letter describing the event

written by William Mein, a slave dealer from Mein, Mackay and Co. of Savannah

states that the Igbo walked into the marsh, where 10 to 12 drowned, while some

were "salvaged" by bounty hunters who received $10 a head from

Spalding and Couper. Survivors of the Igbo rebellion

were taken to Cannon’s Point on St. Simons Island and Sapelo

Island where they passed on their recollections of the events.

The Igbo

Landing site and surrounding marshes in Dunbar Creek are claimed to be haunted

by the souls of the perished Igbo slaves.

![]()

Chatham Manor

– 1805

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA]

The wealthy

William Fitzhugh built Chatham in the three-year period ending in 1771. He was

a friend and colleague of George Washington, whose family's farm was just down

the Rappahannock River from Chatham. Washington's diaries note that he was a

frequent guest at Chatham. He and Fitzhugh had served together in the House of

Burgesses prior to the American Revolution, and they shared a love of farming

and horses. Fitzhugh's daughter, Mary Lee, would marry the first president's

step-grandson, George Washington Parke Custis. Their

daughter wed the future Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

Fitzhugh

owned upwards of 100 slaves, with anywhere from 60 to 90 being used at Chatham,

depending on the season. Most worked as field hands or house servants, but he

also employed skilled tradesmen such as millers, carpenters, and blacksmiths.

Little physical evidence remains to show where slaves lived; until recently,

most knowledge of slaves at Chatham was from written records.

In January

1805, a number of Fitzhugh's slaves rebelled after an overseer ordered slaves

back to work at what they considered was too short an interval after the

Christmas holidays. The slaves overpowered and whipped their overseer and four

others who tried to make them return to work. An armed posse put down the

rebellion and punished those involved. One black man was executed, two died

while trying to escape, and two others were deported, perhaps to a slave colony

in the Caribbean.

A later

owner of Chatham, Hannah Coulter, who acquired the plantation in the 1850s, tried

to free her slaves through her will upon her death. Her will provided that her

slaves would have the choice of being freed and migrating to Liberia, with

passage paid for, or of remaining as slaves with any of her (Coulter's) family

members they might choose.

Chatham's

new owner, J. Horace Lacy, took the will to court to challenge it and had it

overturned. The court denied Coulter's slaves any chance of freedom by ruling

that the 1857 Dred Scott decision by the U.S. Supreme Court had declared that

slaves were property, and not persons with choice.

![]()

George Boxley – 1815

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA]

George Boxley (1780–1865) was a white abolitionist and former

slaveholder who allegedly tried to coordinate a local slave rebellion on March

6, 1815, while living in Spotsylvania, Virginia. His plan was based on

"heaven-sent" orders to free the slaves. He tried to recruit slaves

from Orange, Spotsylvania, and Louisa counties to meet at his home with horses,

guns, swords and clubs. He planned to attack and take over Fredericksburg and

Richmond, Virginia. Lucy, a local slave, informed her owner, and the plot was

foiled. Six slaves involved were imprisoned or executed. With his wife's help, Boxley escaped from the Spotsylvania County Jail and,

despite a reward, he was never caught.

Boxley fled to Ohio and

Indiana, where he was joined by his family. He built a cabin in 1830, the first

in Adams Township. He helped runaway slaves, taught school, and supported

abolitionism.

![]()

Denmark Vesey

- 1822

Denmark

Vesey was born in 1767 , either in America or the

Caribbean; no one is sure. He was living on St. Thomas by the time he was 14. Sugar

Cane was the primary crop and, like tobacco in Virginia and rice in South

Carolina, it was a labor intensive crop. Captain Joseph Vesey had originally

sold Denmark to a French planter, but when Denmark was diagnosed with epilepsy,

Captain Vesey he was compelled by law to buy Denmark back from the planter.

Because of this, Denmark became the personal slave of Captain Vesey and escaped

the labor of the Caribbean plantations.

Captain Vesey had given his personal

slave the name of Denmark because the slave had been part of a shipment from

the Danish colony of St. Thomas.

Captain

Vesey was an experienced slave trader, seeing Africa as just another place of

business. During the acquisition of slaves, Denmark was forced to watch the

Captain examine African men, women and children as if they were cattle. Once

they had been acquired, the slaves were chained below deck of the slave ships –

packed side-by-side – for most of the journey across the Atlantic, which was

known as the Middle Passage. As many as 1/3 of the slaves died from illnesses or committed

suicide during the long, arduous journey.

By the time

Denmark was 16, he had learned all about the evils of the slave trade and its

brutal treatment of the Africans. He also learned of the profits that were made

by the sea captains and slave traders when he sailed with Captain Vesey from

1781-1783. However, with the market for slaves in America beginning to decline

by 1783, Captain Vesey gave up the slave trade and settled in Charleston, South

Carolina. Northern farmers began growing

crops that required less intensive labor than before. In addition, the economic

reasons for abandoning slavery, as well as the moral and ethical reasons,

coupled with the language of the Declaration

of Independence, declaring that “all men are created equal,” made for a

more democratic republic. [NOTE: The first draft of the Declaration of

Independence contained language that strongly condemned slavery, but those

words were ultimately omitted from the final version.]

During the

Revolutionary War, plantation production had been brought to a standstill,

property had been destroyed, and the American currency had become worthless. Denmark Vesey: Slave Revolt Leader, by Lillie J. Edwards. Chelsea House

Publishers, New York, New York. P. 34-35. ISBN: 1-55546-614-1. A great deal of labor was

now needed to rebuild Charleston. Non-slaveowners

could hire slaves for $6 to $10 a month to help in the labor of rebuilding, as

well as helping the railroad men, shipbuilders, merchants, doctors, lawyers,

engineers and many other businessmen in their task to restore the cities to

their former glory. Denmark was a skilled carpenter, and soon found himself

involved in this skill throughout Charleston. Because he was still owned by

Captain Vesey, he turned his salary over to the Captain. However, Denmark commanded much of his time

and worked with less supervision by Captain Vesey as he had on the slave

ships. Captain Vesey paid Denmark with a

portion of the wages he earned, as an allowance. During his free time, Denmark

had the opportunity to read the newspapers, exchange opinions with other slaves

and free blacks, and participate in the lottery. At the age of 32, Denmark won

$1500.00 in the lottery, which was more than enough to buy his freedom. When he

asked to buy his freedom from Captain Vesey, the Captain set a price of $600.00

and scheduled a sale to take place the following month. In January of 1800,

Denmark bought himself from Captain Vesey in exchange for his manumission papers.

Although

these papers were required to prove Denmark’s status as a free man and had to

be carried by him at all times, they did not legally guarantee that he would

not be abducted and sold back into slavery. Although he was now a free man, he

realized that he would never be totally free, due to laws in the South that

allowed slavery. He had to pay two annual taxes – one $10 tax because he was self employed in a trade and the other, a $2 poll tax,

required for residency. Failure to pay these taxes could result in having their

services sold by the sheriff. In addition, free blacks accused of a crime were

tried in the same manner as slaves – without any legal representation and,

instead of a jury, the trial was in front of a judicial committee composed of

two justices of the peace and several landowners, with only a simple majority of

the committee members requiring a conviction and with no right of appeal. Free

blacks also could not serve on a jury or testify against a white. Blacks could

only testify against blacks. Ibid., P.

45-48.

Among many

organizations that sought to protect the rights of free blacks – such as the

Human and Friendly Society, Minors Moralist, the Friendly Union, The Brown

Fellowship Society and the Society of Free Blacks – the most important were the

churches. Denmark’s involvement in a black church caused him to believe that he

had been freed from slavery because he had a special mission in life: to put an

end to slavery.

The wealth

of the South was concentrated among the large plantation owners and was dependent

on slavery. The Northern farms were smaller and produced crops that were not as

labor intensive. Slave labor had never

become an integral part of the North’s economy. The Industrial Revolution was

underway. In the North, industrialization combined with an influx of poor

European immigrants to provide a deterrent to slavery. Ibid., 54. In 1793, industrialization came to the South with Eli Whitney’s invention of the

cotton gin. Work that had once taken a

slave a day to produce a pound of seed-free cotton,

was now a thing of the past. The cotton

plantations of the South now demanded more slaved and, with this demand, the

northerners began to free their slaved or sold them to the southern cotton

planters for profit, causing a southern resurgence in slave trade. The U.S.

Constitution allowed slave trade in the United States until 1808. Old slave

laws that had been enacted in Virginia in 1680 had now become the model for the

entire southern United States. The laws did not allow negroes

to carry arms and provided thirty lashes if a Negro lifted up his hand against

any Christian. Also, if a slave refused to work, escaped or resisted lawful

apprehension, the slave could be killed.

Also in

1793, France abolished slavery within its territories, but did little to stop

the revolution on St. Domingue. In 1804,

the revolutionary forces won their independence and named the new republic

Haiti. The news of the successful revolt in Haiti soon reached the South. After

an unsuccessful slave rebellion in Norfolk, Virginia in 1793, South Carolina’s

governor ordered that all free blacks and people of color that had come as

refugees from St. Dominique the previous year had to leave the state within 10

days. In addition, French refugees from

St. Domingue who came to the United States were no

longer permitted to bring slaves. The

precautions taken to suppress news about the Haitian revolution failed. Since

literate slaves could read about the revolution in newspapers, slaves in

southern cities soon overheard conversations about the revolt. In the spring of

1800, two slaves - Gabriel Prosser and Jack Bowler – had stockpiled weapons for

a planned attack on Richmond, Virginia.

A violent storm interrupted Prosser’s plans and Prosser’s band of slaves were arrested and 35 of them were executed,

putting an end to the revolt. Ibid.,

59-62.

By 1820,

Charleston was the 6th largest city in the United States. The black

population (14,127) now exceeded the white population (10,653) and whites began

to fear of a potential uprising. Patrols were established in all districts and

slave owners were required to serve in the militia after they turned 18. Female

slave owners and those unwilling to serve could pay for a substitute. When the

whites who headed Charleston’s Methodist church took away the black

congregation’s right to meet on its own, Morris Brown, the minister of the black congregation led a secession from the

white church., forming the Hampstead African Church.

In 1816, the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church was created. In 1817, when Morris Brown organized the

African Association in Charleston, they followed the example of the A.M.E. church. Shortly after Brown founded the Hampstead

Church, 469 black worshippers were falsely accused and arrested for disorderly

conduct. In June of the following year, 140 Hampstead worshippers were put in

jail. A bishop and four ministers from the group were given the choice of

spending a month in jail or leaving the state. Eight ministers were also

sentenced to either receive 10 lashes or pay $10 each. Also in 1820, a group of

free blacks from the Hampstead church petitioned the legislature to allow the

church to hold services without white supervision. The petition was denied. The

Hampstead church, however, continued to hold services until 1822, when attempts

to suppress it could no longer be controlled. Ibid.,

71-73.

Although

several efforts were made to appease the white authorities, Denmark Vesey would

have none of it. He was determined to free all black people forever. He chose

to fight. Biding his time, he spent years challenging the slave system. Because

of this many blacks feared retaliation from the white community.

In 1820,

Vesey and a few other slaves began to conspire and plan a revolt. Because Vesey

was now considered a preacher, he recruited other followers and planned revolts

at his home during religious classes. He inspired the others by the tales of

the delivery of the children of Israel from bondage. He planned the

insurrection to take place on Bastille Day, July 14, 1822. This month and day

were chosen because it was the same date that the French Revolution had first

abolished slavery on Saint Domingue. News of the plan

was said to be spread among thousands of blacks throughout Charleston and

for miles along the Carolina coast. Although the black population included a

growing class of people of color and mulattos, Vesey generally aligned with the

slaves, creating a large network of supporters. Later, fearing that word of the

rebellion would surface, Vesey advanced the date to

June 16.

The

insurrection was essentially over before it began. Beginning in May, two slaves

opposed to Vesey’s scheme, George Wilson and Joe LaRoche

gave the first specific testimony about the coming uprising to Charleston

officials, stating the date of the planned insurrection. These testimonies

confirmed an earlier report that had been received from another slave, Peter Prioleau. Officials hadn’t believed the less specific

testimony of Prioleau, but did believe Wilson and LaRoche because of their unimpeachable reputation with

their masters. This testimony caused the city to begin a search for the

conspirators. Charleston Mayor, James Hamilton, organized a citizen’s militia

and many suspects were arrested by the end of June, including 55-year-old

Denmark Vesey. As suspects were arrested, they were held in the Charleston

Workhouse until the newly-appointed Court of Magistrates and Freeholders heard

evidence against them. The Workhouse was also the place where punishment was

applied to slaves for their masters, and likely where

Plot suspects were abused or threatened with abuse or death before giving

testimony to the Court. The suspects were also visited by ministers. Vesey told

the ministers that he would die for a “glorious cause.”

From June 17, the day after the purported insurrection was to

begin, to June 28, the day after the court adjourned, officials arrested 31

suspects, and more as the month went on. The Court took secret testimony about

suspects in custody and accepted evidence against men not yet charged. Some

witnesses possibly testified under threat of death or torture, but the accounts

appeared to provide details of a plan for rebellion.

Newspapers remained silent while the Court conducted its

proceedings. The Court pronounced Denmark Vesey and five black slaves guilty,

sentencing them to death. The six men were executed by hanging on July 2. None

of the six, however, had confessed and each proclaimed his innocence to the

end. Their deaths quieted some of the city residents’ fears and the news in

Charleston about the planned revolt began to die down. No arrests were made in

the next three days.

After that, in July the cycle of arrests sped up and the suspect

pool was greatly expanded. Most blacks were arrested and charged after the

first group of hangings on July 2. Over the course of five weeks, the Court

ultimately ordered the arrest of 131 blacks, charging them with

conspiracy. The arrests and charges in

July more than doubles but the court was finding it increasingly difficult to

get “conclusive evidence,” Three men sentenced to death implicated scores of

others when they were promised leniency in punishment. In total, the courts

convicted 67 men and hanged 35, including Vesey in July 1822. A total of 31 men

were transported (deported or sold into slavery), 2y reviewed and acquitted,

and 38 questioned and released.

The remainder of Vesey’s family was also affected by the Court

proceedings. His enslaved son Sandy Vesey was arrested, judged to have been

part of the conspiracy, and included among those deported from the country,

probably to Cuba. Vesey’s wife Susan later emigrated

to Liberia, the colony established for freed American slaves. Another son,

Robert Vesey, survived through the Civil was and was

emancipated. He helped rebuild Charleston’s African Methodist Episcopal Church

in 1865 and also attended the transfer of power when U.S. officials took

control again at Fort Sumter.

On October 7, 1822, Judge Elihu Bay

convicted four white men for a misdemeanor in inciting slaves to insurrection

during the Denmark Vesey slave conspiracy. They were sentenced to varied fines

and reasonably short jail time. None of these four men were found to be a known

abolitionist. The harshest punishment of the four whites was a sentence of

twelve months in jail and a $1,000 fine.

Two of the other white conspirators were given a $100 fine and

three months in prison, while the fourth received a sentence of six months and

a five hundred dollar fine. Judge Bay sentenced the four white men as a warning

to any other whites who might think of supporting slave rebels. He also pushed

state lawmakers to strengthen laws against both mariners and blacks in South

Carolina in general and anyone supporting slave rebellions in particular. The

convictions of the men enabled the white pro-slavery faction to continue to

believe that their slaves would not stage rebellions without the manipulation

of “alien agitators or local free people of color.”

![]()

Nat Turner -

1831

Nat Turner was born on

October 2, 1800 on the farm of Benjamin Turner in Southampton County, Virginia,

just 5 days before Gabriel Prosser was executed in Richmond. Turner learned to read

and write and, from books, learned how to make paper and gunpowder. He became

religious almost to the point of fanaticism and was recognized as a Baptist

preacher by the slaves and once actually baptized a white man. He was regarded

by the slaves as a leader. In May 1828, the Spirit informed him that, like

Christ, he was to take up the “fight against the Serpent” and that a sign would

soon be given for the “war” to commence.

Nat Turner was purchased

by Thomas Moore upon the death of Benjamin Turner and was now owned by Moore’s

infant son Putnam, but worked for Moore’s widow and her new husband, Joseph

Travis.

The sign that Turner had

been waiting for appeared as an eclipse of the sun in February 1831. Turner

confided with 4 trusted slaves and they agreed to commence on July 4, 1831, but

Turner fell ill. On August 13, 1831, the sun rose with a greenish tint that

later turned to blue and a dark spot was visible on its surface later that

afternoon. This was a taken as a new sign to Turner. A week later, Turner, a

slave named Hark “General Moore” Travis and another slave named Henry Edwards

met at a stream near Joseph Travis’ home. Hark brought a pig and Henry brought

some brandy. Four other slaves joined them and, after drinking late into the

night, they set out on their path of destruction.

When Joseph Travis and his

family arrived home from church close to midnight on August 22, Turner entered

the house soon afterward through a 2nd story window and unbarred the

door to let the other slaves in. They murdered Travis and his family with axes.

Salathiel Francis – owner of the rebels Sam and Will

– was next. He was killed in his farmhouse about 600 yards away. As they went

from house to house, they gathered muskets, swords and other weapons and their

numbers increased from seven to sixty. No white along the route was spared

except one family so poor that, Turner observed, “they

thought no better of themselves than they did of the negroes.” Turner sent a

band of slaves to gather recruits at the farm of James Parker, but the slaves

discovered Parker’s cellar was full of apple brandy and did not return quickly.

Many of the whites were away at a camp in North Carolina and, as the word

spread of the rebellion, a militia was hard to raise.

A militia unit finally arrived from Jerusalem and this proved too much for the

slaves, which dispersed. This defeat at Parker’s field prevented the rebels

from marching on Jerusalem where 300 to 400 women and children had fled for

safety.

That night, Turner tried

to rally his forces and gather new recruits and the next day the rebels

appeared at the home of Dr. Simon Blunt, where the final skirmish was

fought. Blunt had armed his slaves and

they helped resist the rebels, although rumors were that Blunt and his sons did

the work themselves. The rebellion was now over. One Virginian noted that “not

one female was violated.” Only one of

the victims, Margaret Whitehead, was killed by Turner himself. At least four

free blacks had joined the rebellion and one of them – Bill Artis

– in order to avoid execution or sale into slavery, walked into the woods,

placed his hat on a stake and shot himself.

On Tuesday and Wednesday,

as militia units from the surrounding countries arrived at Jerusalem along with

United States troops from Fortress Monroe*, a massacre of the blacks of Southampton began.

Most of the torture and killing was done by vigilante groups, such as a party

of horsemen that set out from Richmond, “with the intention of killing every

black person they saw in Southampton County.” The militia also took part. One

militia unit from North Carolina beheaded a group of prisoners and placed their

heads on poles, where they remained for weeks. The number of blacks that were

killed is unknown, but the number ranges into the hundreds. The massacre

subsided largely because the militia commander, General Epps, quickly disbanded

and sent home the militia and the artillery and infantry units, and strongly

condemned the “inhuman butchery.”

On Wednesday, August 31,

the court of Southampton County convened to try the

rebels. By this time, almost all of them

had been captured except Turner. Varying accounts exists of the fate of the

rebels. One account states that 21 were

hanged, and 16 were sold into slavery. Another account shows that 45 slaves were

tried. Of these, 15 were acquitted, 18 were hanged and 12 were transported out

of the state and sold into slavery.

However, Turner was able

to hide in the woods close to where the rebellion began until Sunday, October

30 or Monday, October 31, when Benjamin Phipps captured him. On November 5,

Turner was convicted and sentenced to hang. He went to his execution six days

later – November 11 - with dignity and composure, refusing to make a final

statement to the crowd that had gathered to watch him hang. The heirs of

Turner’s owner were awarded $375 in compensation by the court. Turner’s body

was flayed (skinned), beheaded and quartered. His headless remains were either

buried unmarked, given to surgeons for dissection, or were rendered into

grease. Souvenir purses were supposedly made of his skin. His skull passed

through many hands, and sat for a time in the biology department at Wooster

College in Ohio. It was last reported as being in the collection for a planned

civil rights museum in Gary, Indiana, despite calls for its burial.

Soon after Turner’s

execution, Thomas Ruffin Gray, the lawyer that defended

Turner at trial, took it upon himself to publish The Confessions of Nat Turner, derived partly from

research done while Turner was in hiding and partly from jailhouse

conversations with Turner before trial. This work is considered the primary

historical document regarding Nat Turner.

*Fortress Monroe would later serve as the site of Jefferson Davis’

incarceration while awaiting trial for treason

The sentencing of Nat

Turner is as follows:

The

Commonwealth

vs

Nat Turner

Charged with making insurrection,

and plotting to take away the lives of divers free white persons, &c. on

the 22d of August, 1831.

The court, composed of -------, having met for the

trial of Nat Turner, the prisoner was brought in and arraigned, and upon his

arraignment pleaded Not guilty;

saying to his counsel, that he did not feel so.

On the part of the Commonwealth, Levi Waller was

introduced, who being sworn, deposed as follows: (agreeably to Nat’s own Confession.) Col Trezvant1 was

then introduced, who being sworn, narrated Nat’s Confession to him, as follows:

(his Confession as given to Mr. Gray.)

The prisoner introduced no evidence, and the case was submitted without

argument to the court, who having found him guilty, Jeremiah Cobb, Esq.

Chairman, pronounced the sentence of the court, in the following words: “Nat Turner! Stand up. Have you anything to

say why sentence of death should not be pronounced against you?

Ans. I have not. I have made a full confession to Mr. Gray, and I have

nothing more to say.

Attend then

to the sentence of the Court. You have been arraigned and tried before this court, and

convicted of one of the highest crimes in our criminal code. You have been

convicted of plotting in cold blood, the indiscriminate destruction of men, of

helpless women, and of infant children. The evidence before us leaves not a

shadow of doubt, but that your hands were often imbrued in the blood of the

innocent; and your own confession tells us that they were stained with the

blood of a master; in your own language, “too indulgent.” Could I stop here,

your crime would be sufficiently aggravated. But the original contriver of a plan,

deep and deadly, one that can never be effected, you

managed so far to put it into execution, as to deprive us of many of our most

valuable citizens; and this was done when they were asleep, and defenseless;

under circumstances shocking to humanity. And while upon this part of the

subject, I cannot but call your attention to the poor misguided wretches who

have gone before you. They are not few in number – they were your bosom

associates; and the blood of all cries aloud, and calls upon you, as the author

of their misfortune. Yes! You forced them unprepared, from Time to Eternity.

Borne down by this load of guilt, your only justification is,

that you were led away by fanaticism. If this be true, from my soul I pity you;

and while you have my sympathies, I am, nevertheless called upon to pass the

sentence of this court. The time between this and your execution, will

necessarily be very short; and your only hope must be in another world. The

judgment of this court is, that you be taken hence to

the jail from whence you came, thence to the place of execution, and on Friday

next, between the hours of 10 A.M.

and 2 P.M. be hung by the neck

until you are dead! dead! dead!

and may the Lord have mercy upon your soul.

1 The committing Magistrate

Source: Great Lives

Observed: Nat Turner.

Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J. Edited by Eric Foner.

Pp. 40-52.

A List of Persons

Murdered in the Insurrection, on the 21st and 22nd of

August, 1831

A List of Negroes

Brought before the Court of Southampton, with Their Owner’s Names, and Sentence

![]()

Creole Case – 1841

[FROM: WIKIPEDIA]

The Creole case was

the result of an American slave revolt in November 1841 on board the Creole, a

ship involved in the United States coastwise slave trade. As 128 slaves gained

freedom after the rebels ordered the ship sailed to Nassau, it has been termed

the "most successful slave revolt in US history". Two persons died as

a result of the revolt, a black slave and a white slave trader.

The United Kingdom

had abolished slavery effective 1834; its officials in the Bahamas ruled that

most of the slaves on the Creole were freed after arrival there, if they chose

to stay. Officials detained the 19 men who rebelled on ship until the Admiralty

Court of Nassau held a special session in April 1842 to consider charges of

piracy against them. The Court ruled that the men had been illegally held in

slavery and had the right to use force to gain freedom; they were not seeking

private gain. The 17 survivors were also released to freedom (two had died in

the interim).

When the Creole

reached New Orleans in December 1841 with three women and two child slaves

aboard, Southerners were outraged about the loss of property. Relations between

the United States and Britain were strained for a time. The incident occurred

during negotiations for the Webster-Ashburton Treaty

of 1842 but was not directly addressed. The parties settled on seven crimes

qualifying for extradition in the treaty; they did not include slave revolts.

Eventually claims for

losses of slaves from the Creole and two other US ships were covered, along

with other claims dating to 1814, in a treaty of 1853 between the US and

Britain, for which an arbitration commission awarded settlements in 1855

against each nation.

Slave Revolt in the Cherokee Nation - 1842

The 1842 Slave Revolt

in the Cherokee Nation, then located in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) west of the

Mississippi River, was the largest escape of a group of slaves to occur among

the Cherokee. The slave revolt started on November 15, 1842, when a group of 20

African-American slaves owned by the Cherokee escaped and tried to reach

Mexico, where slavery had been abolished in 1836. Along their way south, they

were joined by 15 slaves escaping from the Creek in Indian Territory.

The fugitives met

with two slave catchers taking a family of eight slave captives back to Choctaw

territory. The fugitives killed the hunters and allowed the family to join

their party. Although an Indian party had captured and killed some of the

slaves near the beginning of their flight, the Cherokee sought reinforcements.

They raised an armed group of more than 100 of their and Choctaw warriors to

pursue and capture the fugitives. Five slaves were later executed for killing

the two slave catchers.

What has been

described as "the most spectacular act of rebellion against slavery"

among the Cherokee, the 1842 event inspired subsequent slave rebellions in the

Indian Territory. But, in the aftermath of this escape, the Cherokee Nation

passed stricter slave codes, expelled freedmen from the territory, and

established a 'rescue' (slave-catching) company to try to prevent additional

losses.

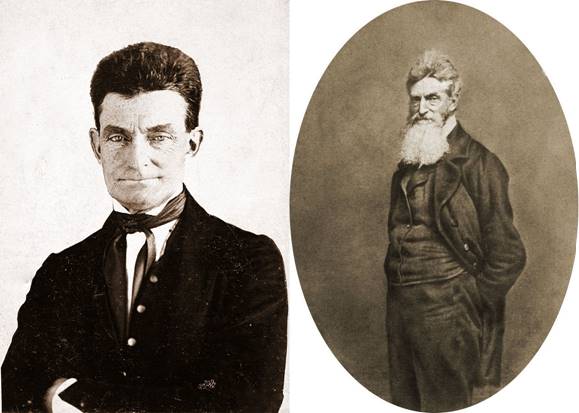

John Brown – 1859

John Brown, an abolitionist from Ohio, came to the Kansas Territory

to fight slavery in October 1855. On November 21, 1855, the so-called “Wakarusa

War” began when a Free-Stater named Charles Dow was

shot by a pro-slavery settler. The war had one fatality, when the free-stater Thomas Barber was shot and killed near Lawrence on

December 6. On May 21, 1856, a posse led by Sheriff Jones of Douglas County,

Kansas, invaded Lawrence and burned the Free State Hotel, destroyed two

newspaper offices and ransacked homes and stores. The home of Charles L.

Robinson, who would later become the first governor of Kansas, was taken over

as Jones’ headquarters.

John Brown was particularly affected by the sacking

of Lawrence because it had been founded by anti-slavery settlers to help insure

that Kansas would become a “free state.” The violence across the area continued

to escalate, earning the state the nickname of “Bleeding Kansas.” Brown led

four of his sons – Frederick, Owen, Salmon and Oliver and two other followers –

Thomas Weiner and James Townsley to plan the murder

of settlers who spoke in favor of slavery. At a proslavery settlement at

Pottawatomie Creek on the night of May 24, 1856, the group seized five

pro-slavery men - James P. Doyle and his two adult sons, William Doyle and

Drury Doyle, Allen Wilkinson and William Sherman - from their homes and hacked

them to death with broadswords, leaving their gashed and mutilated bodies as a

warning to the slaveholders. Brown and his men escaped and later began plotting

a full-scale slave insurrection to take place at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, with

financial support from Boston abolitionists. Brown had originally asked Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass to join him in the insurrection. Tubman was prevented from joining

because of illness and Douglass declined, believing that Brown would fail and

telling Brown “You’ll never get out alive.”

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, Brown detached a party under John

Cook, Jr., to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, the great-grandnephew of George Washington at his nearby Beall-Air estate, along with some of his slaves and two relics of George

Washington: a sword allegedly presented to Washington by Frederick the Great

and two pistols given by the Marquis de Lafayette, which Brown considered

talismans. On the return trip, Brown’s men captured several watchmen and

townspeople at Harper’s Ferry. They cut the telegraph wire and seized a

Baltimore & Ohio train that was passing through. A free black man, Hayward

Shepherd, the baggage-handler on the train confronted the raiders. They shot

and killed him. Brown let the train continue down the line and the conductor

alerted the authorities. Brown had thought that local slaves would join his

group in the rebellion, but word had not spread, as Brown originally

anticipated. Despite this and some resistance from the white community, Brown

and his men succeeded in capturing the Harper’s Ferry Armory that evening. On

the morning of October 17, the Armory was surrounded by local militia, farmers

and shopkeepers. When a company of militia captured the bridge across the

Potomac River, Brown and his men had no means of escape. Four townspeople were

killed that day, including the mayor.

Realizing that his escape was cut, Brown took nine of his captives and

moved into the smaller engine house, which would come to be known as John Brown’s Fort. At

one point, however, Brown sent out his son, Watson, and Aaron Dwight Stevens

with a white flag, but Watson was mortally wounded and Stevens was shot and

captured. The raid was rapidly deteriorating. William H. Leeman,

one of the raiders, panicked and tried to escape by swimming across the Potomac

River, but he was shot and killed. During the intermittent shooting, Brown’s

other son, Oliver was also shot; he died after a brief period.

By 3:30 that afternoon, President Buchanan ordered a detachment of U.S.

Marines to march on Harper’s Ferry under the command of Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee. On October 18, Colonel Lee sent Lt. J.E.B. Stuart under a white flag of truce to

negotiate the surrender of Brown and his followers. Lee instructed Lt. Israel

Greene to storm the engine house if Brown refused. When Brown refused the terms

of the surrender, the Marines’ attempted to storm the engine house, using

sledgehammers against the doors, to no avail. Greene found a wooden ladder and

he and about 10 Marines used it as a battering ram to knock the front doors in.

Once inside, the Marines took Brown and all of his group alive and as their

prisoners within three minutes. Brown

was found guilty of treason against the state of Virginia and was hanged on

December 2, 1859. His execution was witnessed by John Wilkes Booth, who would assassinate President Abraham Lincoln. Over the next few

months, six more of Brown’s gang would be executed.

When John Brown was sentenced to hang in late 1859 for the Harper’s Ferry

Insurrection, Edmund Ruffin made sure to

attend his execution.

Ruffin managed to obtain some of the pikes with which Brown had intended to arm

escaped slaves, and sent them to southern governors with a letter warning them

that the “fanatical Northern party” intended great harm to the South. A song

called John Brown’s Body, was written about Brown’s death and was sung by Union

soldiers as they marched into battle. The

tune was later used by Julia Ward Howe when she wrote The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Thomas J. Jackson gave an eyewitness account

of the execution. On July 21, 1861, Thomas J. Jackson would

acquire the nickname of “Stonewall” at

the First Battle of Bull

Run.

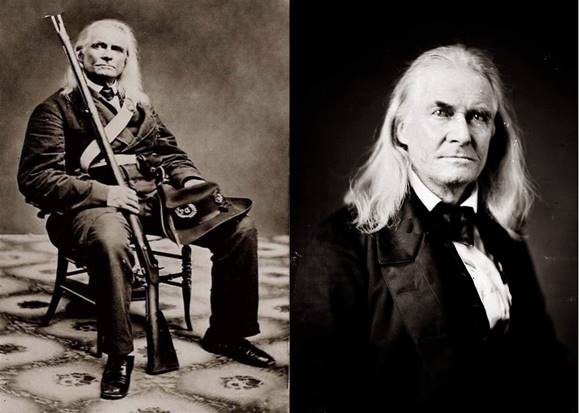

Edmund Ruffin was an outspoken agronomist, secessionist,

and the one to later claim to have fired the first shot in the Civil War. He

was also considered to be the exact opposite of the abolitionist John Brown. Four years later, upon hearing of

Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, Edmund Ruffin was despondent. Plagued by ill

health, family misfortunes, and the rapid collapse of Confederate forces in

1865, Ruffin proclaimed his hatred for the Yankees. As his last expression of the southern code

of honor, the refusal to accept a life in defeat, he wrote in his final journal

entry:

“I

here declare my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule -- to all political, social

and business connection with the Yankees and to the Yankee race. Would that I could impress these sentiments,

in their full force, on every living Southerner and bequeath them to every one

yet to be born! May such sentiments be held universally in the outraged and

down-trodden South, though in silence and stillness, until the now far-distant

day shall arrive for just retribution for Yankee usurpation, oppression and

atrocious outrages, and for deliverance and vengeance for the now ruined,

subjugated and enslaved Southern States!

...And

now with my latest writing and utterance, and with what will be near my latest

breath, I here repeat and would willingly proclaim my unmitigated hatred to

Yankee rule--to all political, social and business connections with Yankees,

and the perfidious, malignant and vile Yankee race.”

On

June 18, 1865, Edmund Ruffin went upstairs to his room, wrapped himself in a

Confederate flag, put a rifle in his mouth, and used a forked stick to press

the trigger. The percussion cap went off without firing the rifle. The noise

alerted Ruffin’s daughter-in-law. By the time she and Ruffin’s son got to his

room, Ruffin had reloaded and finished the job. He is buried at Marlbourne Estate, Hanover County, Virginia.

Suicide Article 1 Suicide Article 2 Suicide Article 3

![]()

Preston Brooks and Charles Sumner

On May 22, 1856, Republican Senator Charles Sumner took to the floor to denounce the threat of slavery

in Kansas and humiliate its supporters. He had devoted his enormous energies to

the destruction of what Republicans called the Slave Power, that is the efforts of slave owners to take control of

the federal government and ensure the survival and expansion of slavery. In his

speech called “The Crime Against Kansas,” Sumner

ridiculed the honor of elderly South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler, portraying his pro-slavery agenda toward Kansas

with the raping of a virgin and characterizing his affection for it in sexual

and revolting terms. The next day, Butler’s cousin, the South Carolina

Democratic Congressman Preston Brooks, nearly killed Sumner on the Senate floor with a heavy cane. The action electrified the nation, brought

violence to the floor of the Senate, and deepened the North-South split.

Brooks’ action was applauded by many Southerners, and abhorred in the North. An

attempt to oust him from the House of Representatives failed, and he received

only token punishment in his criminal trial. He resigned his seat in July 1856

to give his constituents the opportunity to ratify his conduct in a special

election, which they did by electing him in August to fill the vacancy created

by his resignation, He was reelected to a full term in November 1856, but died

five weeks before the term began in March, 1857. Sumner spent months convalescing and finally

returned to the Senate in 1857, but was unable to last a day. His doctors

advised him to travel abroad, and he immediately found relief. He spent two

months in Paris in the spring of 1857 and toured several countries, including

Germany and Scotland before returning to Washington where he spent only a few

days in the Senate in December. After finding himself too exhausted to listen

to Senate business, he sailed once more for Europe on May 22, 1858, the second

anniversary of the Brooks attack. After spending weeks in Paris undergoing

treatments and recovery for spinal cord damage inflicted by the attack, he

finally returned to the Senate in 1859. He died on March 11, 1874. Brooks’ cane used in the attack is now on display at the Old State House in Boston.

Articles Detailing Brooks’ May 22, 1856 Assault on Sumner

Article 1 Article 2 Article 3 Article 4

![]()

NOTE: Since this page is focused on slave rebellions

in the United States, some important rebellions that occurred outside of the

country are not included. Here is a list of some of them:

Gaspar Yanga’s

Revolt – 1570 – Veracruz

St. John Slave

Revolt – 1733 – St. John

Tacky’s War – 1760 – Jamaica

Haitian Revolution – 1791-1804 – Saint-Domingue

Bussa’s Rebellion – 1816 – Barbados

Baptist War – 1831-1832 – Jamaica

Amistad

Ship Rebellion – 1839 –

Off the Cuban Coast

![]()

Confederate States and the Civil War

Site Design Copyright © by Ron Collins. 2015.